| categories:development

The steel industry, file_fdw and the synchronisation of data

Contents

- Steel me.

- On the process of selling metals world wide

- Synchronisation vs. Import

- PostgreSQL, how I love thee

- Using file_fdw with Ecto

- Transform the data

- The key to doing things fast

- Joining external and internal tables

- What to do next?

- Numbers, please!

- So, we use this all the time now?

- Learnings and a repository

Steel me.

My god.

It has been 2 years since I wrote something.

I am really bad at social media.

I also started working as a developer for a company called Klöckner & Co. To be exact, I work for its subsidiary called kloeckner.i, which is focused on bringing the other subsidiaries (Kloeckner France, Kloeckner UK, Kloeckner Metals US and many more), of the group into a glorious, bright and … well, digital future.

We are building tools to help our companies trade and deal with our products - steel & metals - in a digital fashion (as opposed to analog). It’s all about innovation (the “i” in kloeckner.i) and coming up with new ideas on how the industry will operate in 10 years from now. Interesting stuff! If you want to learn more, you can watch our main man, CEO of the group, Mr. Gisbert Rühl himself explaining the concepts of the how and why.

In the meantime, after having built the inital team, I am now working as a the Lead Software Architect in kloeckner.i. For starters, this meant leaving the shackles of management behind and focusing more on the technical implementation of the ideas that our tech and product department provide. In order to understand the challenges we face at kloeckner.i, one needs to understand how the overall business model looks like.

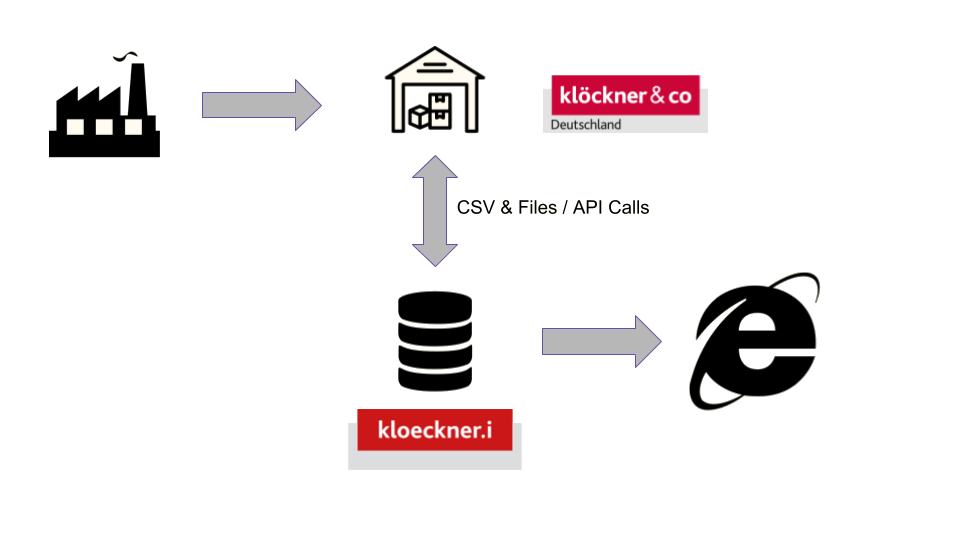

On the process of selling metals world wide

While the processes are different from country to another, the main mechanism stays the same - we buy the steel from a mill (a producer smelting various materials), store it in our warehouses and then deliver it to our customers. For whatever your project may look like, Klöckner can provide the metals necessary to make your dream of a skyscraper reality. Or a bridge. Or yacht. Or you just really like buying a couple tons of steel from us. We got you. At kloeckner.i, we deal with the fact that this business model generates a ton of data, which comes in different forms and shapes. All the services that we provide are powered by this data, sometimes enriched, sometimes raw. Nevertheless, it is always put to use by providing it through applications to the end user.

And since we cannot connect your laptop, mobile phone or PDA (you still have yours, right?) directly to the source of data (the ERP of the country organization), we have to transform it and store it away for usage in our services. The data we get most often comes in the form of structured text: CSV and XML in most cases. Overall, we employ various means of transmitting data from the subsidiaries’ ERP to our services:

- Transmitting files via (S)FTP and then

- Using APIs to allow data push

- Using queueing strategies to distribute pieces of the data to our services

Most of these methods work to varying degrees. For one-time-imports of single files, the straight imports usually work best, as they are simple and easy to understand. APIs are also nice, since you can fend off broken data early. The downside is that not everyone can immediately use an API as actively pushing data is not always possible. Queueing strategies are well understood, but require monitoring and are tough to debug.

The overall strategy, however, stays the same:

Synchronisation vs. Import

Keeping our requirements in mind and the the fact that we need to operate a copy on the data, the challenge here is to keep everything in sync. The external system will provide a data dump somehow and we are tasked to make sure that we have the same data in our systems.

Having realized this, we usually speak of synchronisation at kloeckner.i - and as I set out to find a better solution for our long running imports, while attending the ElixirConf 2018 in Warsaw I watched the keynote by developer Evadne Wu. She dealt with the topic of data imports and called for having a better relationship with our data storage. As it turns out, PostgreSQL offers a ton of useful extra features that I had ignored for way too long.

PostgreSQL, how I love thee

We use PostgreSQL extensively at kloeckner.i. It’s our go-to storage layer and nearly all of our projects include a PostgreSQL in development, usually in the form of a docker container. In fact, most projects look like this when you get into their docker-compose.yml:

version: "3.4"

services:

app:

command: mix do deps.get, phx.server

build: .

ports:

- 4000:4000

depends_on:

- db

db:

image: <gitlab-registry>/infrastructure/postgres:latest

volumes:

- /var/lib/postgresql

ports:

- 5432:5432

Before you type that tweet to the end: latest is just the current version we use for all projects. We are managing the PostgreSQL version used centrally in a custom build image.

Foreign data wrappers

PostgreSQL has the ability to interact with foreign data objects, utilizing its foreign data wrapper feature.

Foreign Data Wrappers are a set of extensions you can use to interact with data sources that are not natively known to PostgreSQL. The full list is quite impressive - and although not everything is stable and supported, the most interesting wrappers are included by default.

file_fdw

Besides funky things like the docker_fdw, there is the very useful file_fdw. There are a couple of these for a multitude of file formats, including PostgreSQLs own pg_dump SQL, JSON, XML and CSV.

Wait, this means…

Using file_fdw with Ecto

Disclaimer: This uses Ecto because Elixir based applications are widespread within kloeckner.i. It has become one of our primary languages and is used throughout all of our teams. You can copy this approach to any other programming language, if you wish.

defmodule SynchronizeApp.Repo.Migrations.AddFileFdwExtension do

use Ecto.Migration

@up ~s"""

CREATE extension file_fdw;

"""

@down ~s"""

DROP EXTENSION file_fdw;

"""

def change do

execute(@up, @down)

end

end

This will create the file_fdw extension. It’s included in the later version of PostgreSQL, you just need to activate it. In another migration, we need to enable a server, a virtual object our table definitions will be bound to later on:

defmodule SynchronizeApp.Repo.Migrations.AddForeignFileServer do

use Ecto.Migration

@server_name "files"

@up ~s"""

CREATE SERVER #{@server_name} FOREIGN DATA WRAPPER file_fdw;

"""

@down ~s"""

DROP SERVER #{@server_name};

"""

def change do

execute(@up, @down)

end

end

I personally advise to use Ecto.Migration.execute/2, in order to have migrations that can be rolled back here. Alas, since the SQL here has no DSL in Ecto itself, we need to resort to executing it directly.

And that is it! We now need to create tables for the CSV files we receive from an external source. For reference, this is what such a file normally looks like:

company_id|name|address1|address2|city|state|zipcode|country

137521| Acme Inc |1381 East I ***20 Access"" Road| pleas, talk to "MAUDE"|Maraune|AK|733-336|United States

11582| Stark Industries|14065 SW 142 ST| |New York|NY|33186|United States

The file_fdw wrapper ideally is fed with RFC4180 compliant CSV. In the real world, years of manual data entry have done some harm to the overall data quality, so we need to clean up here a bit. Also, we do get some weird characters in the files, including quotes ("), which cause havoc when not using an addtional configuration.

Never lose hope, this is all digestable with the options given to the table definition:

defmodule SynchronizeApp.Repo.Migrations.AddForeignCompaniesTable do

use Ecto.Migration

@up ~s"""

CREATE FOREIGN TABLE external_companies (

company_id text,

name text,

address1 text,

address2 text,

city text,

state text,

zipcode text,

country text

) SERVER kmc_files

OPTIONS ( filename '/files/Company.csv', format 'csv', delimiter '|', header 'on', quote E'\x01');

"""

@down ~s"""

DROP FOREIGN TABLE kmc_companies;

"""

def change do

execute(@up, @down)

end

end

The interesting things here are:

SERVER files- this references the virtual server object we created ealier.OPTIONS ( filename '/files/Company.csv', format 'csv', delimiter '|', header 'on', quote E'\x01')- let’s see:filenameis the location of the file to be read, this must be known to the database serverformatiscsv, but can also betext(giving no options for header configuration)header 'on'defines the first line of the file to be a header, similar to how a lot of libraries workdelimiter '|'gives a custom delimiter character, in our case|, a pipe.quote E'\x01'defines the quote character to be a non-printable character that should never pop up in the file to be read. Unfortunately, it cannot be configured to take an empty string.

- all of the column definitions map to the columns of the CSV header - and everything is

text

This, while being a very rigid table that has no types and is less flexible, still gives us the opportunity to query the data directly, using SQL:

SELECT company_id, name FROM external_companies LIMIT 1;

Result:

|name |company_id|

+--------------+----------+

| Acme Inc |137521 |

Sweet.

Note: The options are directly linked to the options for PostgreSQL’s COPY command, which is a very effective tool if you just want to do a single time import of data you have as CSV files.

Transform the data

Since we now have everything available as a table, nothing stops us from utilizing the functions that PostgreSQL gives us:

SELECT TRIM(name), company_id, MD5(CONCAT(company_id, name)) as hash FROM external_companies LIMIT 1;

Result:

|name |company_id|hash |

+--------------+----------+--------------------------------+

|Acme Inc |137521 |b4fa5d3e03248e285c6cc57ac4f4862e|

And it works like a charm. Partitions using WHERE are also possible, but be cautious - there are no indizes to back you up here.

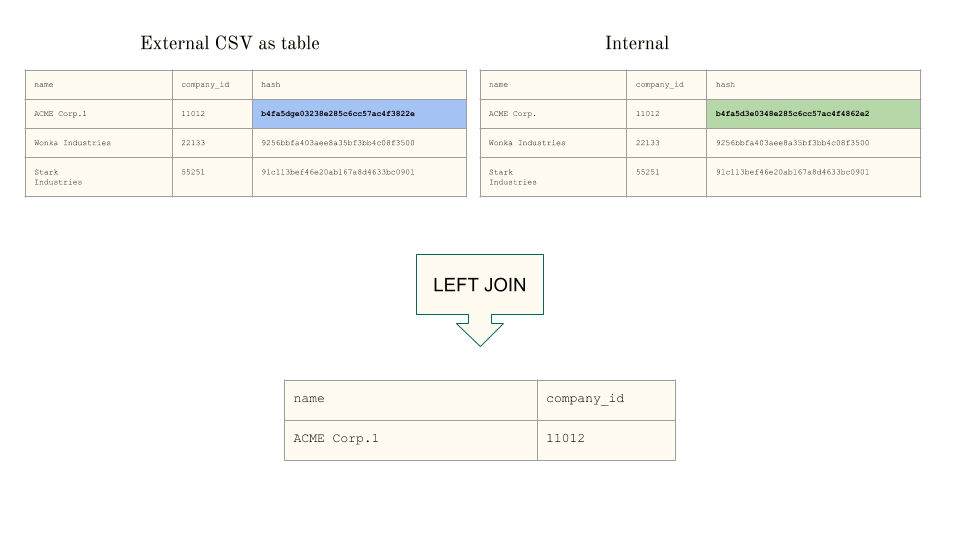

The key to doing things fast

There is a great explanation about why grep is fast - simply spoken: “Being fast usually means not doing a lot of things”, or, to quote:

The key to making programs fast is to make them do practically nothing. ;-)

And it’s true for our usecase as well: When importing data, we should avoid doing things we don’t need to do. And since we keep our CSV files and our service’s tables in one place, there must be a way of finding out the actual workload is. The answer here is: JOINs.

Joining external and internal tables

When having access to tables that should keep the same information, finding the difference over several fields can be done using an SQL JOIN - a full overview over all the joins can be found here. In a more visual fashion, having the csv data as current data, and the internal copied data, we can use a LEFT JOIN to find the differences by joining on a hash created from the fields that we’re interested in:

The full SQL looks a bit scary, but does effectively what is shown above:

SELECT external.company_id, external.name

FROM external_companies external

LEFT JOIN internal_companies internal

ON MD5(CONCAT(external.company_id, TRIM(external.name)))

= MD5(CONCAT(internal.external_id, TRIM(internal.name)))

WHERE internal.external_id IS NULL

It will result in a changeset that we have to digest. In the specific case of having changed Acme Inc to Acme Inc1, we can tell by the changed hash that this record needs to be updated in our service’s data.

What to do next?

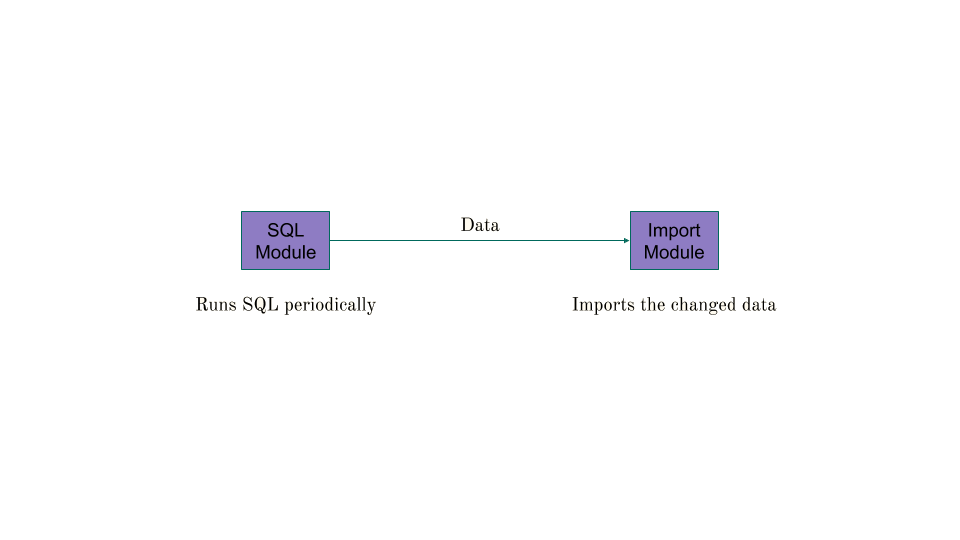

Well, again, Elixir allows use to model this process in very small functions. Visualized by two modules, it can look like this:

We create two modules, one which we’ll call SQLModule that will be used to hold functions that run a Query to determine what the changeset looks like and one that will actually execute insert/update/delete the data in our service tables. Let’s call that one the ImportModule.

Full disclosure: In the real world, we employ data checking and we actually need to grab data from multiple files into a state that makes sense to use it in the tools we built for our customers. That also means, that reality is usually not as simple as it is and we needed to design more complex queries, joining the data of multiple CSVs together.

Let’s have a look at the SQLModule:

defmodule Synchronize.Companies.SQLModule do

@moduledoc """

The module will upsert given companies in batches into the services database.

"""

alias MyService.{Company, Repo}

alias Synchronize.ImportModule

alias Ecto.Adapters.SQL

@doc """

the main entrypoint for this module

"""

def sync do

find_companies() |> run()

end

@doc """

Starts the import for a given set of companies

"""

def run(companies) do

ImportModule.execute(companies, &map/1, &import_batch/1)

end

@doc """

Find missing companies in the services database

"""

def find_companies do

SQL.stream(Repo, """

SELECT external.company_id, external.name

FROM external_companies external

LEFT JOIN companies -- companies is the internal table

ON MD5(CONCAT(external.company_id, TRIM(external.name)))

= MD5(CONCAT(companies.external_id, TRIM(companies.name)))

WHERE companies.external_id IS NULL

""")

end

defp map([external_id, name]) do

now = DateTime.utc_now()

%{

name: String.trim(name),

external_id: external_id,

inserted_at: now,

updated_at: now

}

end

defp import_batch(batch) do

Repo.insert_all(

Company,

batch,

on_conflict: :replace_all,

conflict_target: :external_id

)

end

end

Running Synchronize.Companies.SQLModule.sync/1 will now trigger the query described earlier - whatever changeset is found, will then be given to the ImportModule, which holds functions to execute the mapping necessary (Synchronize.Companies.SQLModule.map/1) and the actual logic to import a single batch of that change (Synchronize.Companies.SQLModule.import_batch/1).

The ImportModule is rather simple:

defmodule Synchronize.ImportModule do

@moduledoc """

The module supports data synchronization from a source of thruth, allowing

transformations

"""

require Logger

alias MyService.Repo

@doc """

Starts the import for a given set of billing addresses

"""

def execute(source, mapper, importer) do

Logger.info("Synchronizing...")

started = System.monotonic_time()

{:ok, count} = run(source, mapper, importer)

finished = System.monotonic_time()

time_spent =

System.convert_time_unit(finished - started, :native, :milliseconds)

Logger.info("Synchronized #{count} item(s) in #{time_spent} millisecond(s)")

end

@batch_size 2_000

defp run(source, item_mapper, batch_processor) do

processor = fn batch ->

batch_processor.(batch)

batch

end

Repo.transaction(fn ->

source

|> stream_row()

|> Stream.map(item_mapper)

|> Stream.chunk_every(@batch_size)

|> Stream.flat_map(processor)

|> Enum.count()

end)

end

def stream_row(source) when is_list(source) do

source

end

def stream_row(%Ecto.Adapters.SQL.Stream{} = source) do

Stream.flat_map(source, fn %{rows: rows} -> rows end)

end

end

Essentially the ImportModule will stream the results from the query, chunk the resulting changeset by a @batch_size and then execute the import function (batch_processor) given.

If we want to further develop this, we can now write several of these SQLModules with their own mappers and processors and use this ImportModule to execute the logic.

NOTE: In reality, the trigger for finding the changeset is centralized on a lockfile which contains a timestamp. The synchronisation process happens when the timestamp changes. We do nothing we don’t really have to do.

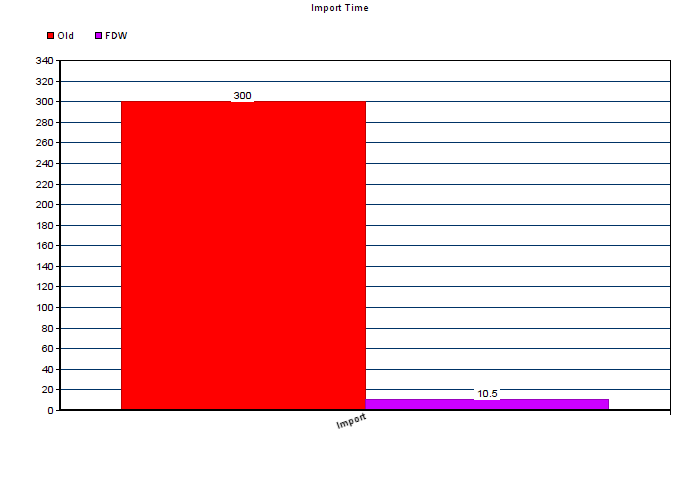

Numbers, please!

While I cannot provide a benchmark here, I can say that switching strategies reduced our import time for this particular piece of customer data from 300 seconds to about 10 seconds average for any given synchronisation process. With the exception of a full synchronisation, which has to process and copy all the data from the external CSV to the internal tables, most of the runs are below those numbers. Nevertheless, here is a graph:

The load on the application is minimal and the actual bottleneck is the database. We use Elixir in this context to delegate and trigger, instead of doing the actual work.

So, we use this all the time now?

No - while this mechanism is interesting, fast and fun to work with (it’s also a great debugging tool for CSV inspection when Excel is just a little to intense to use), the solution has to fit the use case.

In general, you should avoid it, if:

- you only import once

- you don’t feel comfortable using SQL and have extremely complicated transformations

- you don’t have a stable csv definition

- you cannot afford to have business logic tied to your database

The strategy is worth a shot if:

- you need to compare state of several files and the data you have

- you need it fast (PostgreSQLs

COPYis pretty fast) - You want to offload more to your database server

Learnings and a repository

The main thing to take away for our work at kloeckner.i (and for myself) was that PostgreSQL offers so much that it’s almost scary. After having run through many iterations of trying out import strategies we finally found something that fits a lot of our use cases.

If you want to try this and see this strategy in action - I prepared a repo showing the technique with some test data. It runs as two docker containers, so you should be able to use it right away. If you have questions, drop me an email - I’ll be glad to help.

If you completely disagree with all of this, I encourage you to take a look at our jobs page. We’re always looking for smart engineers that can contribute to making the transformation of a whole industry a successful story.

It’s also the best team in the world, not that I might be biased or anything.